Violations of Free Speech Hearings (1940)

#4 (5/11/2023): "Vigilantes" cont'd. (1940 Hearings), Col. Sanborn, Bulosan on Filipino newspapers, Fort Ord Panorama, Spirit Duplicators, Internet Archive Lawsuit (from a Gamer's POV).

Hello,

Work has kept me busy during the past few months, but I’m glad to be able to turn my mind towards this newsletter again.

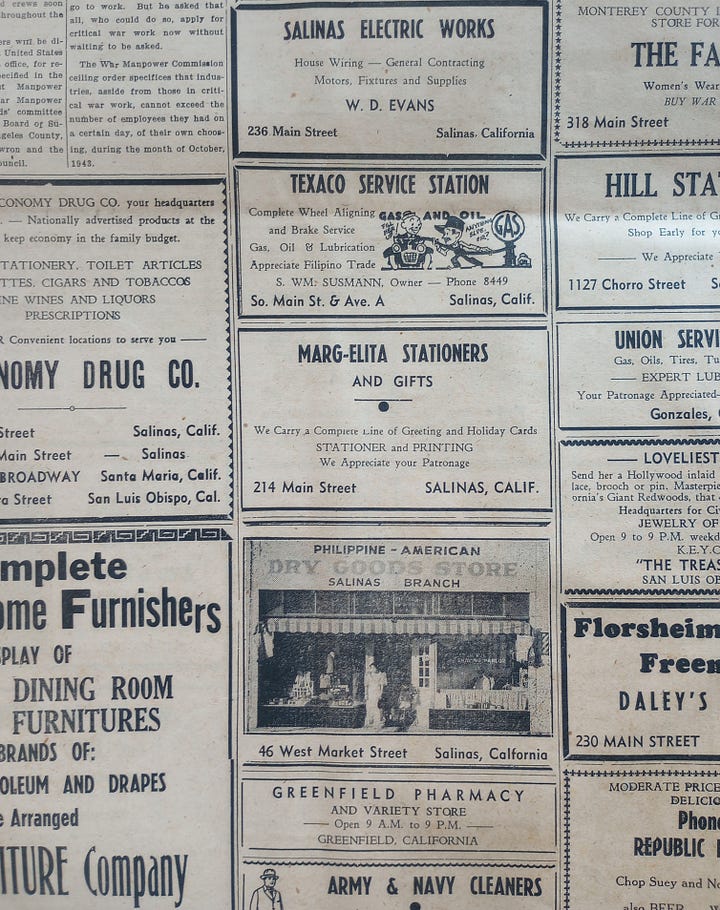

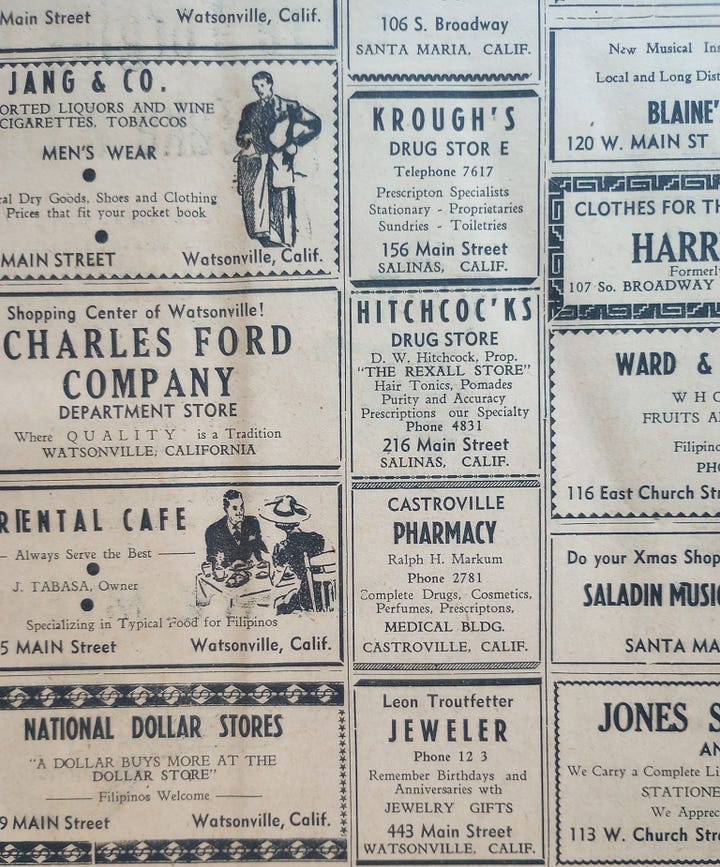

While studying Filipino newspapers from the early 20th century, I sometimes felt frustrated with their general “invisibility.” Considering that Filipinos published over 40 newspapers before WWII, on the West Coast alone, these newspapers are (in my opinion) a fantastic source of information about local community, labor, business, creative, and domestic relationships among U.S. Filipinos in the early 20th century. They also tell you a lot about the dynamics of other immigrant communities existing in relation to the Filipinos—for example, in Salinas Chinatown or Stockton’s Manilatown. You can learn a lot just by reading the ads (which, by the way, are pretty entertaining on their own).

VOICES FROM THE PAST

Hearings: Violations of Free Speech (1940, focusing on events in 1934)1

The events noted in “Vigilantes” (issues two and three of this newsletter) had repercussions through the late 1930s-40s. The Congressional Hearings on Violations of Free Speech (including labor relations in Monterey County) for the events of 1934 provide one source. Below, I include a few excerpts from this lengthy document; but if you are interested, you should really read the original in babel.hathitrust.org.

Hearings: Violations of Free Speech. See sections 7, 8 (etc.) on events of 1934:

P. 27002: Farley Speaks: A history of labor troubles, beginning with difficulties of 1934 which were settled by the Monterey County Industrial Relations board in a decision handed October 9, 1934 and in effect until August 1, 1935, was given by Farley. . . . One of the demands sought by the union at that time was that all sheds be 90 per cent union, a condition to which the shippers could not agree. A contract in every detail the same as the first was signed by both bodies on Sept. 1, 1935, he stated, and under this contract work is now being [carried] on.”

Pp. 27015-25 for the 1934 events (“Vigilantes”), incl. involvement of Sheriff Abbott and police.

P. 27021 for recommendations by Filipino Contractors (Filipino Labor Supply) for how to keep the FLU strikers in line, e. g., “4. Have authorities get rid of important agitators; 5. Delay payment to labor contractors so that laborers would not have the money to spend for drinking and so on” etc.

P. 27039 for Canete’s response regarding the Filipino Labor Supply Association as not being representative of the Filipino workers because of its relationship to the employers.

P. 27041 letter from Luis Agudo (editor of Philippines Mail newspaper (Salinas, CA), a co-founder of the F.L.U.) claiming that the Growers and shippers (in refusing to work only with the Filipino contractors and refusing to talk to the FLU) are using the contractors as “an instrument to disband the Filipino Labor Union . . . and thereby causing two opposing factions among Filipinos themselves. . . .” He also accuses the Growers/Shippers of convincing the Filipino contractors to block the FLU strike in 1933.

Pp. 27044-8 for Agudo’s report about the Sept. 21, 1934 vigilante attack as well as subsequent reports on Canete et al., including a report by the Philippines Mail newspaper. When the FLU split with the VPA, the Shippers and Growers (with backing from Filipino contractors) began to use vigilante force on the FLU union members (in Canete’s camp). Leaders of the FLU were called into the District Attorneys office and met there by police and sheriffs. They were told that the Dept. would be powerless to stop an attack on them, and it would be best if the FLU leaders left town. Their Labor Union office would be raided and all papers destroyed, and union leaders would be killed and/or driven out of town. All pool halls and meeting places in Chinatown (and elsewhere?) were closed so that the FLU could not meet.

ARCHIVES

From the Digital Commons, Humboldt State U., a copy of the American Citizen (Sept. 12, 1936),2 a journal published by Col. Henry R. Sanborn, of Salinas & San Francisco. Note reference to “Reds” in relation to 1934 lettuce strikes; Sanborn had been hired by the agricultural shippers to coordinate strike defenses. The strike was primarily between shed workers and grower/shippers.

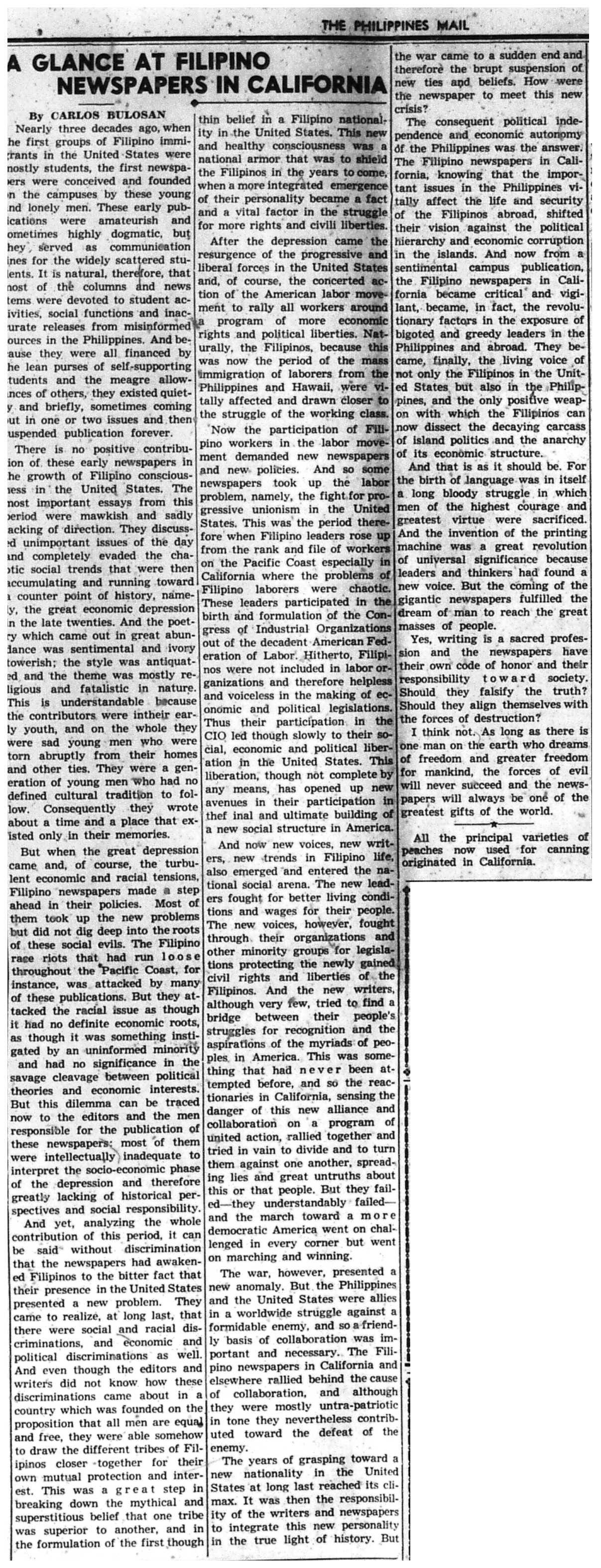

Carlos Bulosan writes about Filipino newspapers in the U.S. after World War II:

The Filipino newspapers in California became critical and vigilant, became, in fact, the revolutionary factors in exposure of bigoted and greedy leaders in the Philippines and abroad. They became, finally, the living voice of not only Filipinos living in the United States, but also in the Philippines. —Carlos Bulosan

In an article published in the Philippines Mail, Writer Carlos Bulosan aimed some pretty harsh criticism at young Filipino newspaper writers in the U.S. He includes among these the Filipino college student magazines and newspapers produced in the U.S. before (and perhaps also during) the Great Depression, such as the Filipino Student, initially sponsored at UC Berkeley (later published out of Chicago). In my own readings, I noticed some of the shortfalls he mentions, the sentimentality and dogmatism, the articles that focused nostalgically on life back in the Philippines. But after reading through many of the newspapers, I also saw continuing efforts to critically examine their own writing and to urge improvement. Bulosan saw the conflicts of the Great Depression era as a chance for Filipino writers to learn about and address larger systemic issues. This article was published in the Philippines Mail (Salinas). An easier-to-read version is available at the Welga Archive - Bulosan Center:

The Fort Ord Panorama was published during WWII. Now available through the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey.

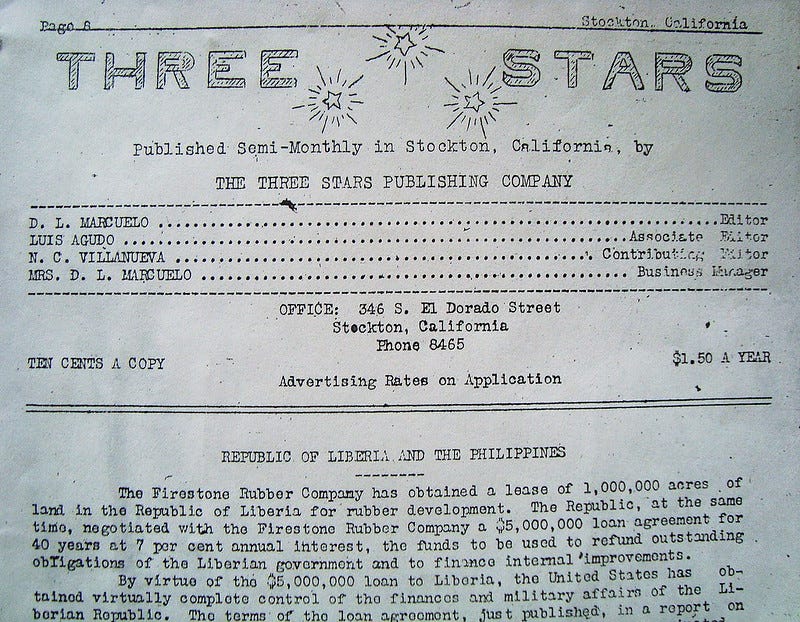

I remember spirit duplicators and their distinctive smell. While the Three Stars was one of the more professional-looking pre-WWII U.S. Filipino newspapers, for a short period they had to print their issues on a spirit duplicator. I’m not sure if it was due to either a lack of money, or a disrupted partnership with a progressive printer (as was the case for the Philippines Mail).

My only connection with spirit duplicators is from my memory of its use in elementary school to distribute worksheets, and I still recall the purple print it produced, and the silky-smooth coated paper one had to use. What I didn’t know is that it was also an early 20th century populist means of disseminating information. A couple decades after the Three Stars was printing their newspaper on the machine, Allen Ginsburg and various Beat poets were producing and distributing their poems copied on spirit duplicators. “Every social justice movement of the 20th century relied on cheap copying technology, coupled with bold (and often crude) graphics to spread their message.”

CURRENTS

Academic archives seem to exist to fortify educational institutions and academics; that has been their priority—not the non-academic community, despite their claims. This outline was produced by the Society of American Archivists. But perhaps some changes are in the works.

The Internet Archive lost its [first] court battle with publishers. This is the Internet Archives side of the story.

This is Mutahar’s3 side of the Internet Archive lawsuit story. And don't let that crazed-gamer-after-too-many-cups-of-coffee look fool you; he actually takes a fairly balanced look at both sides:

There seem to be a lot of seminars and conferences coming up on the topic of AI and its application to archives. Here is the Internet Archive’s blog post on that in “Generative AI Meets Open Culture.”

Thanks for reading Commonwealth Cafe, and big thanks to folks who have recently recommended this site!

Hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Education and Labor, United States Senate, Sixty Seventh Congress, third session, pursuant to S. Resolution 266. A resolution to investigate violations of the right to free speech and assembly and interference with the right of labor to organize and bargain collectively. Part 73, July 1, 1940.

From the Digital Commons, Cal Poly Humboldt State U. (Harris Collection).

Mutahar Anas runs “SomeOrdinaryGamers” on YouTube.