Hello, and welcome to Issue #2 of Commonwealth Cafe!

If you’ve subscribed to this newsletter, you know that you’ll be reading reports from past events, mostly from Filipino newspapers published in the U.S. during the 20th century. I do this because it’s not well known that Filipinos were prolific in their publication of newspapers in the U.S. at that time. I think it’s important to hear these voices; they are an archive, not only of our history, but also of our early literature—poems, essays, short stories—published where they would otherwise not be published in the U.S.

On occasion, I will also include reports from other AAPI and ethnic newspapers of that period, as well as responses to their reports from mainstream news.

This is a work in progress, and I’m looking for the best way to present the material in this format, on Substack, which provides a very supportive public platform for writers and is very different from a website. For now, I’ve got three sections: Voices from the Past (featuring a newspaper clipping); Archival Links (relating to historical Filipino and other AAPI and ethnic newspapers, editors, and writers); and Currents (links relating to today’s ethnic news media, including online and video).

One area I’d like to investigate is how early 20th c. print culture history informs or connects with our understanding of ethnic communities represented in the media today. I started out as an academic researching how literary works were presented in early Filipino newspapers; but, with involvement in a local AAPI community, I’ve begun to see how important it is to make those newspapers accessible to local communities. I hope to include contributions from researchers who would like to contribute their own stories on ethnic media history. Let me know if you’re interested!

VOICES FROM THE PAST

From the Philippines Mail newspaper, published out of Salinas California. The newspaper was published out of Salinas Chinatown, also known then as the “Oriental District.” The Philippines Mail was published from 1934 - 1983, which (to my knowledge) made it the longest running Filipino newspaper in the U.S. In 1934, the newspaper was edited by Luis Agudo and D.L. Marcuelo, but they were then in the process of handing over the reins to someone relatively new to newspaper publishing and writing: Delfin Cruz.

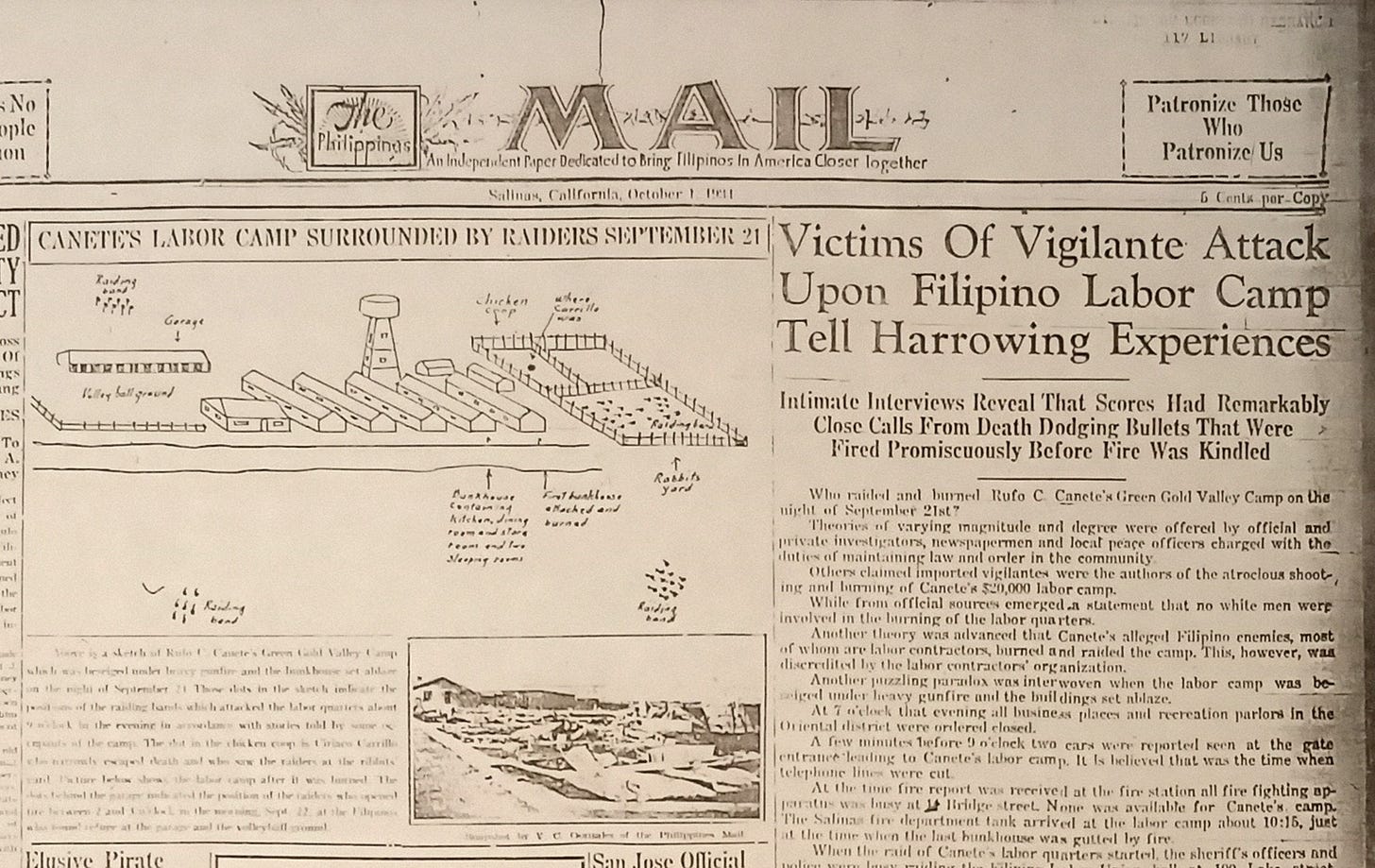

The headline below tells of a vigilante attack on the Green Gold Valley Camp*, in nearby Spreckels, where sugar beets were an important crop. Most of its workers and residents were Filipino, and some were women and children. However, this event took place during the violent Salinas lettuce strike of 1934. The Philippines Mail reported this as “the biggest strike of Filipino fieldworkers in the history of Filipino labor in California.” And indeed, Filipino laborers were being targeted with violence at that time.

Because the type is small and a bit hard to read, I’ve transcribed a portion of the text below.

*Green Gold Valley Camp was managed by Rufo C. Canete, who was also a managing publisher of the Philippines Mail newspaper at that time, and president of the Filipino Labor Union (F. L. U.), whose headquarters were at 100 Lake St., in Salinas Chinatown.

Victims Of Vigilante Attack Upon Filipino Labor Camp Tell Harrowing Experiences

Intimate Interviews Reveal That Scores Had Remarkably Close Calls from Death Dodging Bullets that Were Fired Promiscuously Before Fire Was Kindled.

Who raided and burned Rufo C. Canete’s Green Gold Valley Camp on the night of September 21st?

Theories of varying magnitude and degree were offered by official and private investigators, newspapermen and local peace officers charged with the duties of maintaining law and order in the community.

Others claimed imported vigilantes were the authors of the atrocious shooting and burning of Canete’s $20,000 labor camp.

While from official sources emerged a statement that no white men were involved in the burning of the labor quarters.

Another theory was advanced that Canete’s alleged Filipino enemies, most of whom are labor contractors, burned and raided the camp. This, however, was discredited by the labor contractors’ organization.

another puzzling paradox was interwoven when the labor camp was beseiged under heavy gunfire and the buildings set ablaze.

At 7 o’clock that evening all business places and recreation parlors in the Oriental district were ordered closed.

A few minutes before 9 o’clock two cars were reported seen at the gate entrance leading to Canete’s labor camp. It is believed that was the time when telephone lines were cut.

At the time fire report was received at the fire station all fire fighting apparatus was busy at__Bridge street. None was available for Canete’s camp. The Salinas fire department tank arrived at the labor camp about 10:15, just at the time when the last bunkhouse was gutted by fire.

When the raid of Canete’s labor quarters started, the sheriff’s officers and police were busy raiding the Filipino Labor Union hall at 100 Lake Street. Forty-seven Filpinos in the Union hall, most of whom had gone to bed, were arrested and lodged in jail that night. They were accused of “illegal gathering and inciting a riot.”

While all the conflicting and confusing press reports on “Who raided and set ablaze Canete’s labor camp,” and the whereabouts of the firemen and members of the sheriff’s office and police department at the time of the shooting and burning of Canete’s labor quarters were in progress continue to puzzle the minds of the interested public, some occupants of the ill-fated workers’ bunkhouses offer, by their statements, to unravel the “mystery.”

The caption under the drawing of the camp and next to the photo reads:

Above is a sketch of Rufo C. Canete’s Green Gold Valley Camp which was besieged under heavy gunfire and the bunkhouse set ablaze on the night of September 21. These dots in the sketch indicate the positions of the raiding bands, which attached the labor quarters about 9 o’clock in the evening in accordance with stories told by some occupants of the camp. The dot in the chicken coop is Ciriaco Carillo, who narrowly escaped death and who saw the raiders at the rabbits’ yard. Picture [photo] below shows the labor camp after it was burned. The dots behind the garage indicated the position of the raiders who opened fire between 2 and 3 o’clock in the morning, Sept. 22, at the Filipinos who found refuge at the garage and the volleyball ground.

The type for the interviews is even smaller and less legible, and may take some time for me to transcribe. But I will do my best to present those testimonials in the next issue of Commonwealth Cafe. If you check the link below about the Hanapepe Massacre, in Currents, this was not the first time such an attack on a Filipino labor camp has happened.

ARCHIVAL LINKS

A chapter of my PhD dissertation (2010) focused on Victorio Acosta Velasco, who published several Filipino newspapers in Seattle, beginning with the Philippine Seattle Colonist. Check out Erik Luthy’s article, “Victorio Velasco: Pioneer of Filipino Journalism.” In the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project.

Yet another Filipino newspaper published in Seattle: The Philippine-American Chronicle, edited by Frank Alonzo.

“Hindoo History” is a Substack newsletter by Vishal Ganesan that focuses on Hindu history via archival newspaper clips. Here’s a video of Ganesan’s fascinating presentation on how “Hindoo” culture was introduced to the Western world through print media:

The Fu’ad and Esther Eze are archiving 18,000 days of Nigerian Newspapers on Substack.

CURRENTS

Positively Filipino is San Francisco-based online magazine, one of the most popular news media reporting on the Filipino diaspora experience today. While their title sounds perhaps unremittingly “positive,” they do report on some of the darker aspects of the Filipino experience, as seen in this report/webinar of the 1924 Hanapepe Massacre Mystery, presented by Lloyd LaCuesta:

Joysauce calls itself “a new entertainment platform for American Asians showcasing newly developed dramatic shows, reality TV, great written editorial, podcasts, and curated third party content.”

Social media: History organizations withdraw from Facebook (over its content moderation). Article by Rachael Myrow for KQED.